About Szukalski

Author, sculptor, heretic

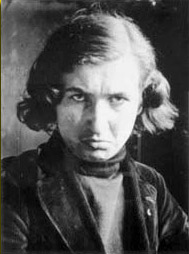

Stanislav Szukalski was born in Warta, Poland on December 13, 1893. When he was only six years old, a teacher sent him to the headmaster’s office for whittling a pencil. The headmaster examined the pencil more closely and discovered that young Stanislav had carved a tiny, near-perfect figure. Instead of punishing him, he called the local newspaper which did a feature on the art prodigy.

Szukalski came to the United States and lived in Chicago when he was in his teens. He became a member of the Chicago renaissance luminaries along with Ben Hecht, Carl Sandburg and Clarence Darrow. Two large monographs were published during those years, The Work of Szukalski (Covici-McGee, 1923) and Projects in Design (University of Chicago Press, 1929).

In the 1930’s, as a celebrated prodigal son to be given his own museum by the Polish government, Szukalski returned to Poland with all his belongings, but his work was cut short by the Siege of Warsaw in 1939. He managed to escape to America to live in California with his wife, Joan Donovan, but his entire life’s work was lost, either bombed or stolen during the War. Now living in total obscurity, he spent the rest of his life obsessively writing and creating art meant to prove a theory that all human culture derived from a single origin on Easter Island after the biblical Deluge of Noah.

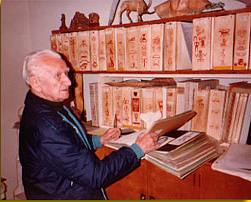

In 1971 his work and existence were rediscovered by Glenn Bray, who became his patron and who later issued two other publications, Troughful of Pearls (Bray/Zwalve, 1980) and Inner Portraits (Bray/Zwalve, 1982). Szukalski died in Burbank, California on May 19th, 1987. A year later his and his wife’s ashes were scattered at Rano Raraku, the sculptors’ quarry on Easter Island by his close friends, some of them fellow artists, Glenn Bray and Lena Zwalve, Robert and Suzanne Williams, and Rick Griffin and Camille Houston. All of Szukalski’s work is now being preserved by Archives Szukalski.

The Neglected Genius of Stanislav Szukalski

By Jim Woodring

Like many another witless child of the American tarmac, I first saw the work of Stanislav Szukalski in issue #1 of R. Crumb’s magazine Weirdo. I was intrigued, but not exactly smitten, and when I found a well-thumbed copy of the Szukalski sampler Troughful of Pearls lying perused and abandoned in the back of a Santa Monica magazine rack I bought it on a whim without any interest in him or his work. Two days later the glacially flowing substance of his genius had slid into my conventional mind and filled it up, transforming me into a raving Szukalski cheerleader who showed his work to everyone I encountered, including total strangers in public places.

When I found out through pure chance that he was alive and living in Burbank, California, scant miles from my own house, I was agog. I looked up his number in the phonebook and called him. When he answered the phone in his deep, mellifluous voice I was so palsied with excitement that I could barely speak, but he was very gracious and when he realized that through my choirboy croaking I was asking if I could visit him he acquiesced warmly.

I had envisioned him living in a comfortable house with a sculpture garden, tended by a doting wife and a small staff of minions and apprentices, dealing nimbly with a steady trickle of art world executors. Instead I found him in a depressingly characterless apartment building, living in two stuffy rooms crowded with statues, personal effects and the clutter of various works-in-progress. His wife had died a few years before and he had no minions, no apprentices, no admiring public. His mainstay and sole major patron was comics art collector and publisher Glenn Bray, who printed Troughful of Pearls in 1980 in an attempt to bring Szukalski’s work before the eyes of the world. As our meeting rolled on, it became horrifyingly evident to me that Szukalski was living in poverty and almost total obscurity.

Yet plainly he was one of the greatest artists of this or any age, a relentless creative force that produced an incredible number of astonishing works during the course of a career that spanned seventy-five years. The story of his life is so interesting, and his list of achievements so extensive, that to give a proper account of them would take volumes. He was born in 1893, achieved recognition as an artist of great promise while in his teens, endured two decades of sickness, hunger and neglect, and had a museum devoted exclusively to his works at forty. He produced hundreds of elaborate and profoundly expressive sculptures and dozens of thousands of drawings; he discovered what he believed was the prototypical language of ancient humanity; he formulated an original anthropological science and substantiated it with forty-two large volumes of drawings and writings; he designed monuments and buildings – and all this he did with a mastery of draughtsmanship and an originality of design that never fails to astonish whoever sees it.

Ben Hecht in his 1954 autobiography A Child of the Century describes the twenty-year-old Szukalski he met in 1914 as starving, muscular, aristocratic and smoldering with disdain for lesser beings than himself. When an influential art critic favored Szukalski’s art studio with his presence and appraisingly touched a statue with the tip of his cane, Szukalski seized the stick, broke it, and roughly threw it and his potential benefactor out into the street. In fact he categorically loathed all art critics and invariably repaid their admirations with profound contempt; the result was a predictable dearth of career.

Szukalski didn’t mind. He continued to toil like a madman, producing one amazing work after another, confident that his artistic and intellectual supremacy would triumph over the cultural gag order that had been imposed on him.

In 1934 he was vindicated. The government of his native Poland declared him “The Greatest Living Artist” and brought him and all his works to Katowice, where the Szukalski National Museum was being built as a monument to his glory. There could be no greater honor for Szukalski, who considered himself to be Poland in miniature and whose heart yearned ceaselessly for his homeland and his people all the time he was in America.

During WWII the Luftwaffe demolished the museum during its first bombing raid on Poland. Szukalski returned to the United States, there to spend the rest of his life in varying degrees of comfort until his death. His reign as “The Greatest Living Artist” had lasted only a few years.

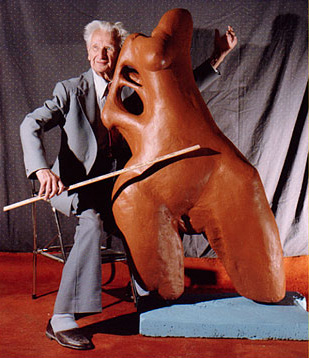

He worked with fierce and single-minded devotion, indifferent to matters of personal comfort or nutrition. When a stroke felled him on May 19, 1987, at the age of ninety-three, Szukalski was still tremendously vital. At an age where the overwhelming majority of Americans are either dead or ruined, Szukalski was a veritable sprite. He possessed an uncommon clarity of mind which age did nothing to obscure. He lived contently alone, walked considerable distances every day for exercise, and managed his own affairs. He could subsist on a diet of cornflakes and water, and yet maintain such muscular strength that his arm felt like a piece of steel drainpipe.

Szukalski possessed a captivating Old World demeanor, and he spoke with a structured elegance that enabled him to put forth his complicated ideas with rich conciseness. He moved along the uncultured slovens of Burbank like a nobleman among savages, anachronistically courtly and polite. He saluted and bowed to men; he kissed the hands of women. A fire burned in his eye at all times, though his mood changed constantly.

He considered himself to be without antecedent or influences. Any suggestion that his work contained, for example, elements of Mayan art was soundly quashed. It is true that he had looked at (and meticulously copied) a fantastically huge amount of Pre-Columbian art and other ancient ethnic images in the course of compiling his work on his science of “Zermatism” (in which he traced the development of mankind’s emergence from the devastation of the Great Flood), but he vehemently denied that his work contained any received ideas or motifs. He was serious about maintaining his claim to a pristine artistic bastardy; he intended to call his autobiography Self-Born.

During my first meeting with him he had me continually off-balance. What is your nationality? he asked me moments after we settled down on chairs in the dank aquarium of his living room.

“Dutch, mostly,” I said.

“The Dutch are the world’s leading proponents and producers of child pornography,” he replied.

Lamely I tried to explain that I wasn’t that sort of a pervert but he bored deeper and deeper into the framework of my personal and ancestral history, determined to make me realize that I belonged to a doomed society of ne’er-do-wells. And yet we parted amiably and remained friendly until his death, because although his conviction that I was an inferior being was genuine, he did not hold that against me. For my part I regarded him as a genius, and extraordinary man who had earned the right to have even his most outlandish notions treated with respect.

During the last decades of his life Szukalski yearned for recognition and exposure, for the admiration and support he had known so briefly and so belatedly and which was now utterly denied him. He saw graffiti artists elevated to the status of exalted masters while he remained isolated from fame as if by an iron wall.

Glenn Bray and Szukalski’s other friends took Troughful of Pearls around to the museums in and around Los Angeles with the expectation of attaining for him the exposure he so manifestly deserved. Museum officials were never anything less than flabbergasted by the quantity and quality of the works. Curators who condescendingly granted five minutes of their time to the book-carriers would end spending an hour or more pouring over the material, gaping in disbelief and trying to comprehend the fact that Szukalski was almost completely unknown.

But nothing ever came of these attempts! The curators ultimately handed back the books with polite thanks and said that they did not care to bring the works of Szukalski into their galleries. Why? Because he was too political, too opinionated, too naked, too crazy.

That word “crazy” came up frequently during these negotiations and it wasn’t intended as a compliment. Szukalski’s philosophical edifice was preposterous. Among his most strongly held (and extensively documented) theories was the notion that a race of malevolent Yeti have been interbreeding with humans since time out of mind, and that the hybrid offspring are bringing about the end of civilization. As proof of this he pointed to the Russians. He also believed that heat causes gravity and that all modern languages derive from Polish. He harbored sentiments that seem fascist and racist, and which were based upon his most patently absurd theories. He was almost certainly wrong about a lot of things; but as anyone who spent any time with him can tell you, he wasn’t crazy.

Szukalski said that his work was rejected because it was so powerfully informed by the tremendous passion he felt for his subjects. He said that average Americans didn’t love or hate anything strongly, as he did, and that they (that is, we) could not appreciate the great themes captured in the writhing sinews of his sculptures and pictures. I think he was to some extent right about this; however, it is evident that the major reason for his continued non-acceptance was that Szukalski simply refused to make himself palatable. He held a lot of unpopular opinions and he saw no reason to keep them to himself. In fact, it was exactly at these moments when a little tactful reticence could have been greatly beneficial to his career that he was most voluble. One time I arranged to bring him to meet with the curator of a major Los Angeles museum. The man’s office was hung with works by Picasso, Matisse, and Kandinsky; Szukalski immediately launched into a sneering tirade against these masters. The curator simply left the room and a secretary showed us out.

A few years back it was arranged for him to give a public address and slide show at a rented hall. About seventy people showed up. Szukalski was ecstatic. He loved to hold forth and he felt affectionate toward his every audience. He mounted the podium and within four minutes had alienated or offended everyone in the place. In his opening remarks he praised Reagan to the heavens and dumped all over Picasso (he pronounced it “Pick-ass-oh”; he denigrated art collectors, Russians, FDR, California, America and professional sports, and wound up with a stern denunciation of “homos.” Audience members glowered and muttered harsh replies into their lapels but when the lecture was over he received a thunderous and prolonged ovation. They had come to realize that Szukalski was not a man to be judged by conventional criteria; they had applauded him as an outstanding member of their species.

During his last years Szukalski’s major project was a gigantic and complex structure that he wished the U.S. to give to France to reciprocate for the Statue of Liberty. He called it the Rooster of Gaul and he had it worked out down to the tiniest detail, including an ingenious plan for paying for it. I remember when he first showed me the model sculpture he had done for the centerpiece of the thing. “Look,” he said, indicating a weary and anguished woman being ravaged by a roiling mass of stylized and inscribed tentacles. “That is the woman who symbolizes France. She is being crushed and ensnared by all the “-isms” of modern Europe. There is Fascism, and there is Communism … and there is Ventriloquism.”

The idiosyncratic particulars of his works notwithstanding, Szukalski’s message is one of faith in oneself. His life was spent in the service of his vision of nobility. He was a man who would not compromise on matters of principle. He was prepared to starve to death rather than accept a scrap of bread under false pretenses. His art is animated by palpable forces of scruple and opinion that are seldom seen in works of the heart, and the messages are so powerfully put forth that lesser minds than his must frequently decline to try to deal with them. He could abide any opinions contrary to his own if only they were strongly held; the thing he detested above all was weakness. And justly so, as it happens, for it turned out that weakness was the very thing that defeated him — the weakness of cultural arbiters who would not dare to buck the tide and be responsible for his becoming known.